Guide to Doing Local History

Best Practices, Conventions, and Policies

This developing guide presents a compendium of best practices, policy suggestions, and practical advice for local history organizations, public historians, and amateur history enthusiasts who want to capture, preserve, and share artifacts, research, and historical news about their communities.

ADVOCACY

Local historians promote all aspects of history. Not only are local historians subject-matter experts who educate the public, but they are also community leaders whose passion and enthusiasm for history should inspire others to critically think about and appreciate the past.

EDUCATION

Local historians function as public educators. Their work should educate, entertain, and inspire us to value and appreciate not only historical artifacts but also the people, events, and socio-cultural, political, and economic processes that shape history. The most important question local historians should address is, “So what?” they can do this by helping the public better understand history through key concepts:

historical significance

primary source evidence and documentation

context

causes and consequences

continuity and change

interpretation through multiple perspectives

ETHICS

Local historians maintain high standards. Historians are guided by codes of ethics and best practices established by professional organizations such as the National Council on Public History (NCPH), American Historical Association (AHA), or the Oral History Association (OHA). For example, the AHA publishes a “Statement on Standards and Professional Conduct” defining the ideals of the history profession, shared values of historians, rigors of scholarship, plagiarism, ethics in teaching, and the important value history to the public. Historians at all levels–from research scholars at universities to small town historical society volunteers should be aware of and practice doing history ethically.

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

When a local history museum or heritage society is an official 501(c)(3) charitable incorporation, governance of the organization typically rests with a Board of Directors. Some charitable nonprofits choose to have an executive director to manage day-to-day operations, lead fundraising efforts, and act as a spokesperson for the organization.

When it comes to understanding who owns a charitable nonprofit, legal experts say that no single person or group of people (including the Board of Directors) can actually own the organization. Nonprofits cannot offer stock, dividends, or equity to anyone.

So what does a Board of Directors do? According to the National Council of Nonprofits:

Board members are the fiduciaries who steer the organization towards a sustainable future by adopting sound, ethical, and legal governance and financial management policies, as well as by making sure the nonprofit has adequate resources to advance its mission.

DUTIES OF DIRECTORS

NCN further states that Boards are guided by three fundamental duties:

Duty of Care

Take care of the nonprofit by ensuring prudent use of all assets, including facility, people, and good will.

Duty of Loyalty

Ensure that the nonprofit’s activities and transactions are, first and foremost, advancing its mission; recognize and disclose conflicts of interest; make decisions that are in the best interest of the nonprofit corporation, not in the best interest of the individual board member (or any other individual or for-profit entity).

Duty of Obligation

Ensure that the nonprofit obeys applicable laws and regulations; follows its own bylaws; and that the nonprofit adheres to its stated corporate purposes/mission.

Local history museums and historical societies have to think about support and sustainability. Here are some proven ways to involve the community so that local historians can “keep the lights on:”

MEMBERSHIPS

Become a museum member and help support our community-wide effort to capture, preserve, and share our local history. Most history museums are tax exempt, charitable 501(c)3 organizations. Membership contributions are tax deductible to the fullest extent of the law.

DONATIONS

Cash and in-kind donations are always beneficial helpful, and they maybe tax deductible.

VOLUNTEERS

Most local history museums are all-volunteer organizations that depend on community volunteers to keep things functioning by doing a wide range of things:

- Be a docent: Be an ambassador for the museum and provide tours and presentations during our many events throughout the year.

- Be a curator. Help design, build, and maintain displays of local interest. Research and catalog donated artifacts.

- Be a fundraiser. Help find resources and develop local support for the museum. Search for available grants, underwriters, and advertisers.

- Be a communicator. Create articles and news stories for our website and social media. Be part of our podcast team.

SPONSORS

Local history museums should offer sponsorships to help support their mission and programming.

ADVERTISERS

Museums can also offer advertising at events, throughout the museum, and within digital media such as videos and podcasts. As with sponsorships, advertising is a great way for an organization to show its commitment to local history.

The American Alliance of Museums encourages organizations to develop the following five core documents that are “fundamental for professional museum operations and embody core museum values and practices. They codify and guide decisions and actions that promote institutional stability and viability, which in turn allows a museum to fulfill its educational role, preserve collections and stories for future generations, and be an enduring part of its community.”

Mission Statement

- Asserts the museum’s public service role

- States why the museum exists and who benefits as a result of its efforts

- Bears date approved by the governing authority

Institutional Code of Ethics

- Aligns with the museum’s governance structure and discipline

- States that the general ethical principles apply to the governing authority, staff, and volunteers and addresses issues specific to each group

- Addresses both the institution’s basic ethical responsibilities as a public trust and the conduct of individuals associated with the institution

- Is a single document tailored to the museum

- Bears date approved by the governing authority

Strategic Institutional Plan

- Current and multi-year

- Aligned with current mission

- Articulates a strategic vision and goals as well as actions steps to achieve them

- Covers all relevant areas of museum operations

- Identifies the human and financial resources required to carry out the plan

- Assigns responsibility for completion of action steps

- Includes information about how success will be measured and evaluated

- Bears date approved by the governing authority

Disaster Preparedness and Emergency Response Plan

- Includes preparedness and response plans for all relevant emergencies and threats (natural, mechanical, biological, and human)

- Addresses the needs of staff, visitors, structures, and collections

- Specifies how to protect, evacuate, and recover collections in the event of a disaster

- Assigns individual responsibilities for implementation during emergencies

- Lists contact information for relevant emergency and recovery services

- Bears date of last revision

Collections Management Policy

- Defines scope and categories of collections

- Acquisitions and accessioning (including criteria and decision-making authority)

- Deaccessioning and disposal (including criteria and decision-making authority)

- Loans, incoming and outgoing (if the museum does not lend or borrow, it should state this)

- Collections documentation and records, including inventory

- Collections care and conservation

- Access and use of collections

- Responsibility and authority for collections-related decisions

- Statement on the use of funds from deaccessioning

- Bears date approved by the governing authority

PROFESSIONAL WRITING & SPEAKING

In most situations, formal writing and speaking standards should apply whenever local historians are communicating with the public, fellow historians, and professionals on behalf of their museums. Hallmarks of effective communication typically include language use that is clear, concise, and accurate. But effective communication is also appropriate for the context or situation. For example, in public settings and on the internet, it’s best to assume that communications should be formal. This means paying attention to grammar, punctuation, spelling, word choice, sentence structure, paragraph organization, and tone.

OUTREACH

Local history museums and historical societies should prioritize public outreach and heavily promote and market their organization and programming (e.g., events, activities, exhibits). Museums can and should use every possible communication channel to promote themselves: newsletters, membership mailings, brochures, articles in local newspapers, history talks, museum tours, and by using the internet for social media and a website.

DIGITAL MEDIA

The internet is a powerful and cost effective way of communicating not only with our local communities but with the entire world. Some would argue that in these times the internet is an essential communication tool. Digital media such as photographs, maps, manuscripts, etc. are convenient alternative forms of capturing, preserving, and sharing historical artifacts and assets. In fact, creating digitized historical artifacts is the only way some history can be preserved.

SOCIAL MEDIA

Local historians have discovered the power of social media platforms to improve outreach in their communities and to share history in digital form. Photographs are especially popular items on social media platforms such as Facebook pages. Self-created videos about local history are very popular as well, cost effective to produce, and easily shared with others. Perhaps social media’s most powerful feature is that it is interactive, giving the community an opportunity to share information and opinions with local historians.

Respect and Collegiality

A note of caution about discourse on social media: History posts can be wonderful opportunities for historians and the public to discuss information and ideas, including alternative historical perspectives and competing points-of-view. In a public forum, this should be done respectfully and collegially. Personal attacks are never warranted, and offensive or rude behavior should not be tolerated.

Social media posts are the property of their creators; generally, they are not free speech zones; people do not have a right to say anything they like unless permitted by the owners of the sites in accordance with the rules of the social media platforms. In most cases, local historians have the power and right to moderate their content on social media and uphold a higher standard of communication.

However, for anyone who wants to filter their posts and control who sees and comments on them, they should create their own social media pages and moderate content as they see fit. Moreover, if anyone takes issue with free and open discourse, especially regarding local history, they might consider not posting to social media groups and pages that permit members and/or the public to comment on posts in accordance with group rules and community codes of conduct.

CURATION

A basic plan of action for any artifact is to fully document its existence. This can be as detailed as desired, but some basic information is essential. For example, with photographs historians want to know title, name of photographer, place, persons in the photo, date taken, manner and purpose of the photograph, pre-existing collection, name of donor, etc. For other items, it’s important to note manufacturer name and location, date, material, description of usage, and name of donor.

ORGANIZATION

It is essential that museums have some way of organizing curation data and storing artifacts so that items can be systematically searched and located.

PRESERVATION

Nothing lasts forever, so it is important that museums store and handle artifacts in such as way that minimizes wear and tear, as well as degradation caused by the elements.

PROTECTION

When it comes to artifacts such as old photographs, audio recordings, film, and documents, one of the biggest misconceptions is that everything old is in the “public domain” and therefore does not have a copyright owner. In other words, it is free to copy, manipulate, and use by anyone.

Another misconception is that artifacts found on the internet are also free to cut/copy/paste by anyone. If an image belongs to someone else, such as a museum, it doesn’t matter if the form is paper or digital, the artifact is legally owned by the museum.

Asserting copyright control and ownership over artifacts in their legal possession is one way in which local historians can safeguard the integrity and use of the artifact. Stipulations of use and other terms can be asserted by museums to protect their artifacts.

SHARING

When historians share artifacts with the public, it is best practice to include as much explanatory information as possible. For example, photographs should always be accompanied by basic curation info (e.g., date of image, photographer, location, identification of persons and activities).

Local historians have an obligation to ensure that professional best practices are followed regarding the proper documentation and citation of artifacts, especially on the internet and social media sites where amateur history enthusiast too often share artifacts such as photographs with little to no identifying documentation. This mishandling of historical information (although not intentionally malicious) undermines the significant time and effort by historians who understand the need to properly document the historical record for other scholars, researchers, and the public.

RESOURCES

- Inventory 101: What is inventorying and why does it matter to museums?

- Museum Inventory (Wiki)

- National Park Service Museum Handbook

- Library of Congress Preservation Resources

- National Archives: Archival Formats – practical advice on preserving a variety of materials: photographs, negatives, and film; paper and parchment; books and scrapbooks, digital and electronic media; and audio and video tapes and motion pictures.

- Historical Society of Pa Resources for Small Archives – information and resources for small repositories about managing archival collections as developed by the staff of the HCI-PSAR project.

HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE

Local history works best when everyone in the community contributes and takes responsibility for capturing, preserving, and sharing our heritage. However, not everything that is old has historical value or significance. But, before disposing of anything you suspect might be of interest to LBHS, please contact the museum.

Items that might have historical significance include:

- Personal diaries, letters, scrapbooks, postcards, or other such non-commercial documents, especially if they relate to major historical events such as the world wars, the Great Depression, etc.

- Documents of local businesses or organizations such as ledgers, membership rosters, oaths, inventory, price lists, etc.

- Old photographs, slides, film reels, and audio recordings of significant events, notable people, or even everyday life if the artifact is exceptionally representational.

- Physical items such as household goods and appliances, industrial tools, political memorabilia, etc.

As a practical matter, museums can’t possibly take in every old item, so historians will have to review and evaluate each item to determine whether it should be discarded or taken in by the museum. It is extremely helpful if owners can provide complete documentation or descriptive information about items.

EXHIBITS & EVENTS

Local history museums typically offer a wide range of exhibits and events throughout the year. The challenging role of local historians is to create programming that entertains, educates, and inspires the public to think more critically about history and to better appreciate its impact on us today. Perhaps the greatest challenge for historians is to shape history into a thoughtful, compelling, and meaningful narrative story. As Rudyard Kipling said, if history were taught in the form of stories it would never be forgotten.

DIGITAL CONTENT

A widely held point of resistance to digital media in local history is that it should never replace physical artifacts, live docents, and tactile experiences found in “brick and mortal” museums. This is true, but the inclusion of digital media into museum programming is never at the expense of physical artifacts. Instead, digital media is complementary, supportive, and value-added programming. Local historians can and should use digital media as a creative and strategic tool to help tell history’s story in new and exciting ways.

Furthermore, digital media has practical benefits such as providing access to museums around- the-clock and with world-wide reach. Through the internet, local history programming is available to all–at home, on the go through mobile devices, in classrooms, and to researchers and scholars.

Recommended Resource: Cohen, Dan, and Rosenzweig, Roy. Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web

Social Media

Local historians have discovered a popular and significant internet side-channel for programming through social media platforms such as Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook. In most cases, the use of these platforms is free, but subject to their advertising, rules about content/expression, codes of community standards, and operational algorithms.

Historians present content (e.g., photographs) via social media posts to share information, encourage discussions, and to enhance outreach with their communities and members. Social media posts are to be considered as interactive digital exhibits. The comments that go along with social media posts are very important as a valuable opportunity for crowd-sourcing information that can add to the historic record. As with any exhibit, these posts should include descriptions, supporting documentation, and source citations. For instance, photographs should be identified as to date taken, photographer, persons and activities in the image, and source or collection in which the image can be found.

Furthermore, under certain circumstances, history organizations retain some level of copyright control over the content they present via their posts. Exhibits (i.e., the arrangement and presentation of information and artifacts, even content in the public domain) are protected by copyright. In other words, if an organization or historian creates a unique image gallery, digital document, or collection of artifacts, these exhibits themselves are owned by the creator, although some of the individual items used to create the exhibit may not be (e.g., items in the public domain). Local history organizations should place a disclaimer on their site and posts as to the permission(s) they grant regarding the copy and use of their posted content by 3rd parties. See: How Copyright Works with Social Media

Suggestion for Creating Effective Social Media Posts

- Posts should be creative, educational, and entertaining. They should have a purpose that fits into the mission and scope of the museum.

- Avoid pointless artifact dumping or meaningless trivia. Answer the question: Why is this object, person, or event historically significant?

- Don’t post content without descriptions and citations as to source archive, owner, dates, explanatory narratives, etc.

- Post should adhere to standards of professional writing, including appropriate grammar, punctuation, and coherent sentence and paragraph structure.

- When posting multiple items to a post (e.g., photographs), attach identifying information to each photo, not just the main post.

- Mark the content with copyright status (e.g., Source: LBHS Image Archive, Townsend Collection. All rights reserved.).

- Don’t plagiarize or pirate content. It’s ok to share others’ social media posts (as they’ve written them), but don’t steal images or text from them. In other words, do not cut and paste photographs or other media directly from another organizations’ social media posts for use in creating your own post.

- Historians should moderate their posts to maintain a high standard of ethical communication.

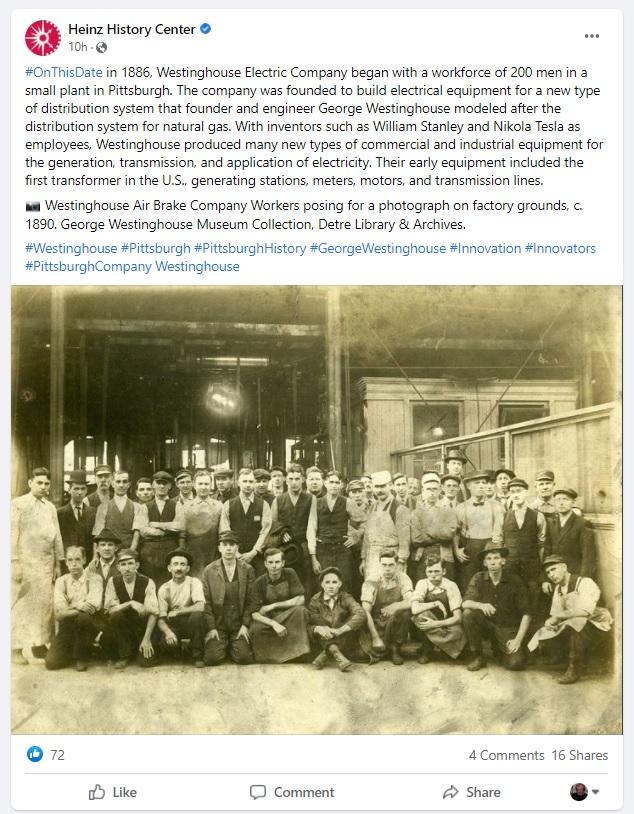

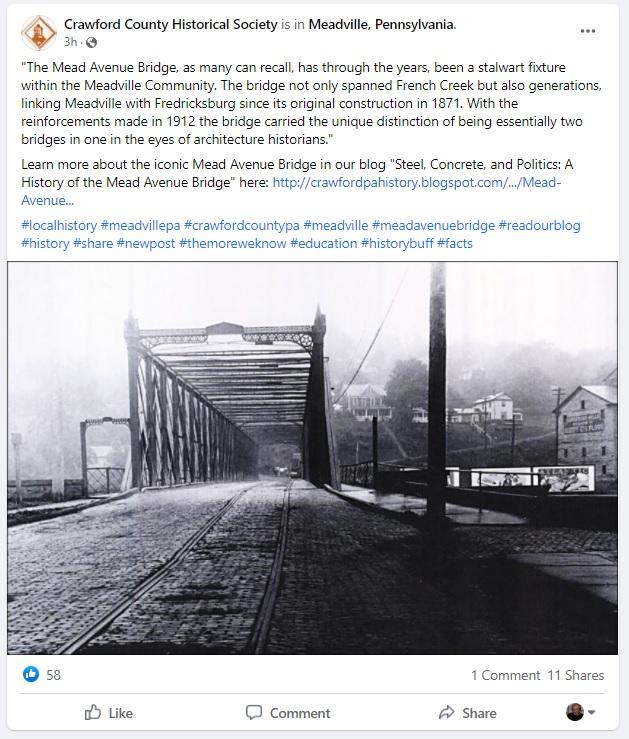

Examples of Effective History Posts

Below are examples of very high quality, effective social media posts by the Heinz History Center (Facebook, January 8, 2022) and the Crawford County Historical Society (Facebook, January 9, 2022). Each is sufficiently documented and thoroughly explained, well written, yet succinct. Note how the photographs and text mutually support of the topic. In addition to being factually informative, these posts provide insight as to why their subjects are historically significant–an essential goal of public history.

Beaver County Local History Directory

| LOCATION | ORGANIZATION | ADDRESS | PHONE | INTERNET |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aliquippa | B.F. Jones Memorial Library | 663 Franklin Ave.Aliquippa Pa. 15001 | 724-375-2900 | Website |

| Ambridge | Ohio Valley Lines Model Railroad, Library & Museum | 1225 Merchant Street, Ambridge, 15003 | 724-266-4787 | Website |

| Ambridge | Old Economy Village | 270 16th Street, Ambridge, 15003 | 724-266-4500 | Website |

| Ambridge | Performing Arts Legends Museum | 1426 Merchant St, Ambridge, PA 15003-2275 | Website | |

| Beaver | Beaver Area Heritage Museum | 1 River Road Extension, Beaver, 15009 | 724-775-7174 | Website |

| Beaver | Beaver County Genealogy and History Center | Beaver Station, 250 East End Avenue, Beaver, 15009 | 724-775-1775 | Website |

| Beaver | Saint Nicholas Chapel | 5400 Tuscarawas Road, Beaver, 15009 | 724-495-3400 | Website |

| Beaver Falls | Beaver Falls Historical Society and Museum | Beaver Falls, PA 15010 | 724-774-6229 | |

| Beaver Falls | Larry Bruno Foundation Hall of Achievement & Museum | 1112 7th Avenue, Beaver Falls, PA 15010 | Website | |

| Brighton Township | Brighton Township Historical Society | 245 Park Road, Beaver, 15009 | 724-774-8292 | Website |

| Chippewa | Air Heritage, Inc. Museum and Aircraft Restoration Facility | 35 Piper St #1043, Beaver Falls, PA 15010 | 724-843-2820 | Website |

| Chippewa | McKinley Schoolhouse | McKinley Road & 37th Street Extension, Beaver Falls (Chippewa), 15010 | 724-843-8177 | Website |

| Darlington | Beaver County Industrial Museum | 801 Plumb Street, Darlington, 16115 | 724-312-0831 | Website |

| Darlington | Little Beaver Historical Society – McCarl Industrial & Agricultural Museum – Greersburg Academy – Little Beaver Museum – Hamilton Forge & Foundry – McCoy Log Cabin | 710 Market Street, Darlington, 16115 | 724-843-4361 | Website |

| Ellwood City | Ellwood City Area Historical Society Museum | 310 Fifth Street, Ellwood City, PA 16117 | 724-752-2021 | Website |

| Enon Valley | Enon Valley Community Historical Society | 1084 Main Street, Enon Valley, 16120 | 724-336-5194 | |

| Fombell | Fombell Area Historical Society | 102 Hardy Lane Ellwood City Pa. 16117 | 724-971-6580 | Website |

| Freedom | Beaver County Historical Research & Landmarks Foundation – Vicary Mansion – Beaver County History Coalition – Beaver County History Online | 1235 Third Avenue, Freedom, 15042 | 724-775-1848 | BCHRLF Website Beaver County History Online Website |

| Homewood | Homewood Heritage Society | |||

| Hookstown | South Side Historical Village | Hookstown Fair Grounds, 1198 State Rt. 168, Hookstown, 15050 | 724-573-9367 | Website |

| Independent | The Social Voice Project – Local History Podcast Initiative – Beaver County Art & History Online Museum – Public History Matters Blog | Internet | 412-423-8034 | Website |

| Independent | Beaver County Past, Present, Future! | Internet | ||

| Independent | Beaver County Pennsylvania History & Genealogy | Internet | ||

| Independent | Georgetown Steamboats | Internet | Website | |

| Independent | Jeffrey Snedden, Historian & Writer – “History in a Minute” video series | Internet | ||

| Independent | Logstown Associates Historical Society | Internet | ||

| Independent | Ambridge Memories: Memories of Ambridge, Pennsylvania (1950-1970–and the years that came before) | Internet | Website | |

| Independent | PICRYL Beaver County Photo Collection – The World’s Largest Public Domain Media Search Engine | Internet | Website | |

| Independent | FamilySearch: Beaver County, Pennsylvania Genealogy | Internet | Website | |

| Monaca | Beaver County Model Railroad and Historical Society | 416 6th Street, Monaca, 15061 | 724-843-3783 | Website |

| Monaca | Baker-Dungan Museum/Millcreek Valley Historical Society | 100 University Drive, Monaca, PA 15061 | 724-573-4895 | Website |

| Monaca | Monaca Community Hall of Fame | 1098 Pennsylvania Avenue, Monaca, PA 15061 | 724-728-0248 412-671-1086 | |

| New Brighton | Historic Grove Cemetery | 1750 Valley Ave., New Brighton, PA 15066 | 724-843-2960 | Website |

| New Brighton | Merrick Art Gallery and Museum | 1100 5th Avenue, New Brighton, PA 15066 | 724-846-1130 | Website |

| New Brighton | New Brighton Historical Society | 1229 7th Ave. New Brighton PA. 15066 | 724-622-8877 | Website |

| Rochester | The H.C. Fry Glass Society | |||

| Rochester | Rochester Area Heritage Society Museum and Model Railroad | 350 Adams Street, Second Floor, Rochester, 15074 | 724-777-7697 |

- National Council on Public History

- Oral History Association

- American Historical Association

- The American Association for State and Local History

- The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC)

- PA Museums

- Pennsylvania Association of Nonprofit Organizations

- National Trust for Historic Preservation

- Preservation Pennsylvania

- Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office (PA SHPO)

- HeritagePA

- PA Museums

- Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media

- Pa Statute Title 37:Historical and Museums

- National Museum of Industrial History